In a long continuance of poverty, and long habits of dissipation, it cannot be expected that any character should be exactly uniform. There is a degree of want by which the freedom of agency is almost destroyed; and long association with fortuitous companions will at last relax the strictness of truth, and abate the fervour of sincerity.

— Samuel Johnson (on William Collins)

There was a long period of time when I categorized creative writing as a job, like any other. As I grew up though, it became more and more obvious that this simply was not the case. They don’t work steady hours, they often work from home, or at the very least not out of an office. They often take years, or fractions of years, to put out content.

Really, you could have a lot of fun with this line. Writers often don’t get published. They’re often rejected many times first if they actually are published. It’s a flooded market, because everyone thinks it’s easy to write a novel. Even if you do manage to push out 50 000 words or more, it’s not easy to make them any good. And even if they are good, good isn’t good enough, especially for a publisher. Especially for the market. Especially for history. What was I getting at?

Right. So you put out a book. Does it even sell well? Maybe you put out another? I read that it took one writer eight novels to start making a livable income.

The more I learned about it, the less likely it seemed that someone anyone was about to list “writer” as their occupation. It’s just so unlikely.

The Split

It wasn’t until nearly a year ago that I realized that there’s a split in books. It’s going to seem really obvious when I say it, but I’m really good at not noticing obvious things so I’ll lay it out for you.

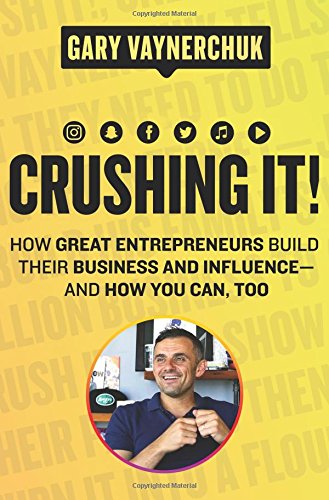

I had been listening to Gary Vaynerchuk for a long time. Eventually I had gotten his entire message down, and he was starting to get repetitive. (Gary, for those of you who don’t know, is marketing entrepreneur who sells the “work hard” message, and talks about how it’s way easier to “make it” now that the internet exists.) I got his first book, Crush It!: Why NOW Is the Time to Cash In on Your Passion on audible, and I listened to it at work. It’s a pretty compelling title, right? The book essentially encapsulates on how to execute on the idea of what is now known as “influencer marketing.” You make a blog, or a youtube channel, or something. Then you become an expert on a topic. Then you just put out content as frequently as you can and build an audience. Apparently it works, because he’s released an updated book on the same thing complete with success stories.

Back to the split. I decided, hey, I can do that. Thus, this blog was started. It wasn’t too long later that I started to realize what I was doing wasn’t the same kind of thing as other influencer blogs were. I’m not talking about anything. I don’t have a specialty. I don’t really have a “brand.” I’m not influencing anyone on anything, not really. I just write stories. Unless I build an audience, nobody’s going to advertise on that, and advertising revenue is kind of the whole thing. It’s hard enough to build a financially successful blog, but building a financially successful fiction blog is essentially unheard of.

To be honest, I don’t know much about fiction blogs. I don’t think you can monetize them in the same way as informational blogs (no affiliate ability, products you can create are limited), so I can’t be of much help. I’m sorry!

— An email reply to my question of how to monetise.

And that’s the split.

Non-fiction is a lot easier to sell than fiction, and as far as I can tell, this extends out of blogs and into books. It’s a lot easier to get a non-fiction book published and have it actually make money. People seek information and solutions to problems a lot more than they seek stories. Those who read for pleasure are a minority; even if you give it away for free, as I and a few other bloggers do.

Let’s keep going.

Great Writers

Studying English Literature at University, I noticed something surprising. A lot of the fiction writers that I studied also had some other job. I can’t really remember many off the top of my head, but I compiled this cool chart. As my definition of “great” I chose people in the canon, and the canon I used was the first one I could find online. You think there’d be a more official list than Wikipedia, but this isn’t really an academic paper, so you’ll have to excuse my use of the free encyclopedia. (Actually, if anyone has a good link to an English or Western canon list, please tell me.)

| Writer | Artistry | Other Occupation |

| Jonathan Swift | Poetry, Prose | Priest, Essayist |

| Samuel Taylor Coleridge | Poetry | Philosopher |

| Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) | Prose | Entrepreneur, lecturer, publisher |

| Edgar Allen Poe | Prose | Critic* |

| William Shakespeare | Poetry, Plays | Actor*, editor |

| Charles Dickens | Prose | |

| William Wordsworth | Poetry | |

| Fyodor Dostoyevsky | Prose | Military engineer, journalist |

| Arthur Conan Doyle** | Prose | Physician, Fancy Moustache |

| John Milton | Prose | Polemicist, civil servant |

| Emily Dickinson | Poetry | Lived with her parents |

| Ernest Hemingway | Prose | Revolving door of rich wives |

| John Donne | Poetry | Priest, lawyer |

| William Blake | Poetry, Painting | Printmaker |

| Miguel de Cervantes | Prose, Poetry | Soldier, accountant |

| Geoffrey Chaucer | Poetry | Bureaucrat, diplomat |

| Virginia Woolf | Prose | Publisher, critic, essayist |

*May not count

*May not count

** Not in a canon

The man who managed to make it into the canon with an unfinished book was the first person who tipped me off. For whatever reason, I remember Geoffrey Chaucer being introduced in class as a banker. but this was two years ago, so, looking at my chart, it seems that I mixed that up. Chaucer was a bureaucrat and diplomat, and he “audited and kept books on the export taxes, which were one of the Crown’s main sources of revenue” (Greenblat 189). I guess he did do something with money.

So, once you realize that people, even the people you learn about in academia, are working as well as writing, you start to think. At least I did. I started to notice more of them here and there. Although, I didn’t much pay much attention to it. Not until this year, when I was researching Poe.

Edgar Allen Poe managed to scrape his gothic self into two separate courses of mine this year. And, looking into him a bit, I learned that “Poe was the first American writer, as Alexander Pope had been the first in England, to support himself entirely by his writing” (Mayers 138). This quote is kind of cool, because it shows that in two separate countries, making a living writing was unusual… for centuries.

Continuing with Poe, however, it seems that even after he “made it,” he continued to struggle financially.

A young author, struggling with Despair itself in the shape of a ghastly poverty, which has no alleviation — no sympathy from an every-day world, that cannot understand his necessities, and that would pretend not to understand them if it comprehended them ever so well — this young author is politely requested to compose an article, for which he will “be handsomely paid.” Enraptured, he neglects perhaps for a month the sole employment which affords him the chance of a livelihood, and having starved through the month (he and his family) completes at length the month of starvation and the article, and despatches the latter (with a broad hint about the former) to the pursy “editor” and bottle-nosed “proprietor” who has condescended to honor him (the poor devil) with his patronage. A month (starving still), and no reply. … At the expiration of six additional months, personal application is made at the “editor’s” and “proprietor’s” office. Call again. The poor devil goes out, and does not fail to call again. Still call again; — and call again is the word for three or four months more. His patience exhausted, the article is demanded. No — he can’t have it (the truth is, it was too good to be given up so easily) — “it is in print,” and “contributions of this character are never paid for (it is a role we have) under six months after publication. Call in six months after the issue of your affair, and your money is ready for you — for we are business men, ourselves — prompt” (Poe).

Poe struggled because editors avoided paying him, and because of a lack of international copyright law. Publishers and magazines could literally just steal works from other countries like Britain, instead of paying the American for his stories. As far as I know, neither of these issues exist anymore. At least, I hope not.

A lot of the great writers had jobs… in fact, if my quote has any weight to it, all writers born before the eighteenth century in England, and the nineteenth in the United States had jobs. For me that means a couple of things. The first is that writing “on the side” is normal. The second is that, even (especially?) if you happen to be extremely artistic, writing anywhere except on the side mightn’t ever factor in.

While I was researching for this, I found a an entire Wikipedia (again) page on physicians who write. I’m not sure why this is a thing, but it’s common enough to have its own page. Mental Floss also did an article on it. So, why not go be a doctor like your parents (may have) wanted you to? Make a six figure income and write in your fancy home during your off hours. Ahah.

Novels are a Business

There isn’t enough money to go around… sort of.

According to Price’s law, half of all scientific contributions are made by the square root of the total number of scientific contributors: thus, if there are 100 scientists within a given discipline, just 10 of them will account for 50 percent of all publications. The Price’s law describes unequal distribution of productivity in most domains of creativity (Gorny, emphasis mine).

The bigger you are, the more people recognise you. The more people recognise you, the more people buy your books. The more people buy your books, the bigger you get. The more people want to publish you. The more stores shelf your book. It’s a vicious cycle, and it’s present in the novelling, and almost any other market.

Most of us aren’t recognised at the top, in fact most writers probably aren’t making anything. There’s probably a large amount that are just writing for fun. Those that are making a living wage are what I like to call the exceptions.

The Exceptions

Writers like J.K. Rowling, Stephen King, and Agatha Christie are the exceptions. Especially Christie. If you want a good example of an exception to the rule, look no further than the woman competing in sales numbers with William Shakespeare!

Outsold only by the Bible and Shakespeare, Agatha Christie is the best-selling novelist of all time. She is best known for her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, as well as the world’s longest-running play – The Mousetrap.

From what I can tell, which isn’t much, it seems to me that there are two ways to actually make money writing. The first is to write a lot of things that are interesting to read. They don’t have to be particularly good, in fact being literary slows you down. Get rid of all that and just write a ton. That’s clearly what Christie did. One of the things that stabbed out of the page at me while reading Harry Potter was the unimpressive and sometimes just plain bad prose. Apparently King isn’t much better. But really, writing in this fashion clearly works if you have the content to make up for it.

There’s another group that manages to get by with fairly simple writing, the occasional grammar error, and lots of releases. It’s the indie publishers. Self publishinh directly to ebooks and cranking out two or three novels a year, these people are on a mission, and it’s paying off. Royalties are lower, if not non-existent if you indie publish, and because it’s digital you don’t even have to pay for printed books. But, the breakneck speed at which you have to release to make a living seems to cut into their quality. I’m not sure.

Conclusion

This is actually sort of an awful article, it spells out how almost exactly how unlikely it is that anyone will make a living writing. It’s the last thing I wanted to hear, that’s why it took a strong three years for me to come around and face it. But, I kind of cheated when I did.

The first thing I pointed out here, in different words, was that it’s unusual to make money doing art. I feel like that’s so obvious that it’s almost in the realm of common sense. Writing somehow falls to the side of that though, possibly because when people think “art” they don’t immediately think “novel.”

Anyway, my first point was that even a lot of the great writers from the canon also did other things, and that’s where I “cheated.” It’s unlikely that you or I will make a living writing. It’s unlikely that anyone will make a living writing. Especially if you want to take the time to put out something of literary quality. So the cheat is that… that’s normal. You don’t have to worry about it, or stress about how you’re going to do it.

I mean, feel free to try, just be careful that you don’t fall into the dead prose of mass fiction… or do, whatever works. As for me, I’m going to try what Margret Atwood did. (Although, I’m not a huge fan of Atwood, she definitely both made it, and is good enough that I read her work in university.) That is, get a “real job” and hope for the best after that. I think it beats being a starving artist working a minimum wage job anyway. And being educated certainly doesn’t hurt writing quality.

Further Reading

I found this article, I thought it was pretty cool. It’s a very strong resource for learning how to make money in art, although it’s geared a little more towards visual arts. The #1 Reason Artists Fail At Making a Living Selling Art (And What You Can Do About It)

I did a post a while back on theme. That might interest you.

Works Cited

Gorny, Eugene. “Price’s law.” Dictionary of Creativity: Terms, Concepts, Theories & Findings in Creativity Research / Compiled and edited by Eugene Gorny. Netslova.ru, 2007. http://creativity.netslova.ru/Price~s_law.html

Greenblatt, editor. The Norton anthology of English literature. Ninth ed., vol. 1 2, W.W. Norton, 2013.

Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: his life and legacy. Cooper Square Press, 2000.

Poe, Edgar A. “Some Secrets of the Magazine Prison-House,” Broadway Journal, February 15, 1845 (accessed at http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/poe/etext/smprison.htm)

Wikipedia. “Western canon.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 9 Feb. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_canon.

Daniel Triumph.

Please check out my most recent work of fiction, Mariça.

3 responses to “Can You make a Living as a Writer?”

Who reads literary fiction. The situation might be better in the West, though not very much. In Asia and the Middle East, hardly around 10% of the population is interested in any form of creative activity. In that, there are music, poisonous TV shows, popular films and other popular entertainment. A fraction turn towards reading. Majority into genre fiction, mostly shoddy. I do not have a real acquaintance who enjoys top notch, prize winning fiction and I live in a city. So, to whom does a good writer sell his works to. Too many writers, too few readers.

Right, and that’s why I said that successful fiction tends to fall into the category of “plain prose.” You might as well call it genre fiction.

As for literary fiction, well, if people were interested in art, then there wouldn’t be starving artists. Literary fiction might be fore a minority, but the goal of transcendent literature is a valuable pursuit. At least, it is for some.

Yes. That is right. Like all art forms literary fiction is transcendental not only on a personal level. On a civilizational level as well. It is a part of humankind in a way genre fiction somehow is not.